Reprinted from Mom Egg Review, Book Reviews, June 21, 2016

by Rosalie Calabrese

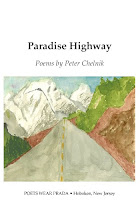

Poets Wear Prada, 2015, $12.00 [paper]

ISBN 9780692303795

Review by RZ Wiggins

Mothers are simple,

complex, opaque, vivid, loving, distant, devoted, and neglectful, all in

a lifetime. From its first pages, this slim volume overflows with the

above and with a mother’s abundant love and commitment. Rosalie

Calebrese’s chapbook Remembering Chris is a

memorial to a lost son. But the collection also shows the many sides to

mothering through a voice that is at once surprisingly pragmatic and

refreshingly honest.

Aside from “Mixed Emotions” (3) which centers on mothering concerns (how many mothers haven’t felt these?), Remembering Chris’s

poems ring with joy at both motherhood and grandmotherhood. Given the

absence of any mention of siblings, it appears that Chris, the

collection’s focus (a boy who loved his Lionel trains), is an only

child.

The poems explore a mother

who dutifully nurtures her son and teaches him what is needed. There is

the heartfelt sting of sternly eradicating obscene words and gestures

and the angst of removing the stowaway from the back seat to again

deposit him at sleepover camp. These are a mother’s duties that must be

done even though the heart is heavy.

I wanted more glimpses into

this bond, more details of days spent together in the boy’s younger

years, his falls and scrapes, more about his young mother. What were

their rituals? Cozying together reading books in bed? Baking cookies on

stormy days? Whispering to a favorite teddy bear in the dark?

Where the boy is absent,

there is much of the mother: a divorced parent struggling to adjust to

her new single status; a woman juggling work commitments and the

coexistent guilt:

…I ran the shuttlebetween career and motherhood.So often, our line of communicationfilled with static − almost disconnected;I feared you’d lose your way. (16)

In addition, there is the

struggle to hold onto some of herself, to be the woman who can go to

Europe without her son while carrying a mother’s guilt.

The woman inside these

poems finds it difficult to tell her granddaughter “what Jewish people

believe in” (19) and instead defers to the Internet. Yet, Jewish

heritage bleeds across the pages, particularly in one of Calabrese’s

most poignant poems:

A Memo to My SonYou had no bris,And you had no bar-mitzvah,But make no mistake, my son:You are the flesh of my flesh,And the blood of my blood:When all the scores are tallied,You will still be a Jew. (8)

Time and again Calebrese

reminds us that mothers must be many things: loving yet stern, strong

yet fallible. They must bend to meet life as it arises before and after

their children are born and especially after a child sadly passes on too

soon. Without a doubt, the essence that shines through these poems is

of the richness and devotion of a mother’s love despite all of life’s

varying circumstances. They remind us that mothers never let go, not

when they send you to summer camp, nor when career demands intrude, nor

when you get married and move into your own home. Mothers swell up with

joy and hold on forever— “I reach for your hand/and hold the memory”

(24).